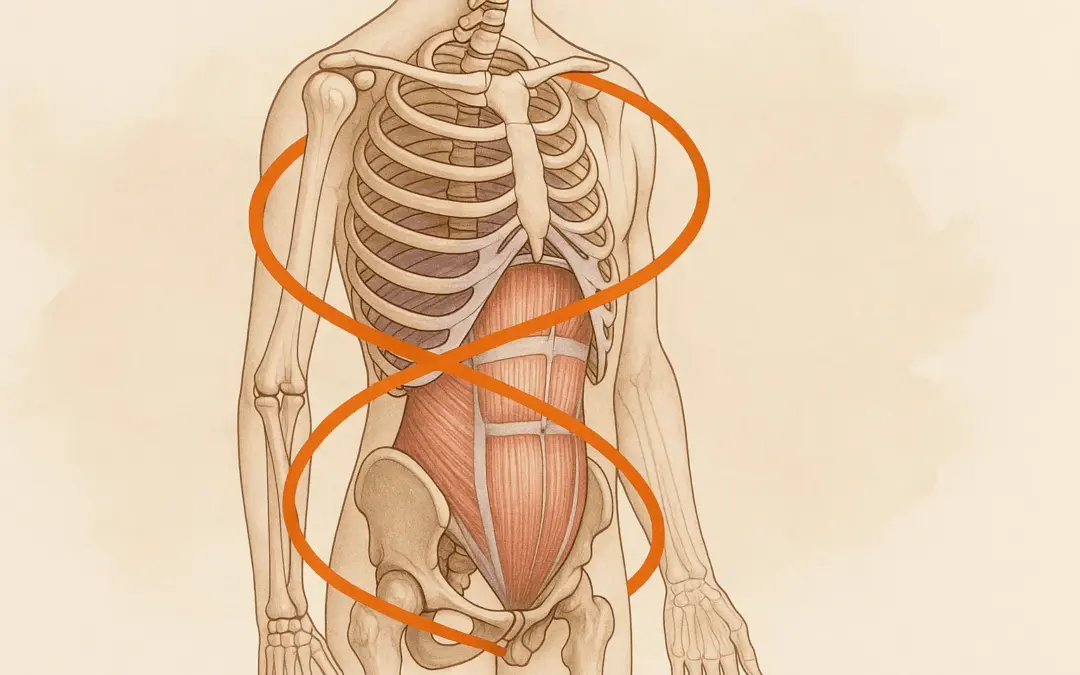

Your body is a complex, living framework designed to stabilize, rotate, and transfer force in every movement you make. At the center of this system is the axial skeleton—your spine, rib cage, and pelvis—which forms the foundation for balance, posture, and movement power. Whether you are walking, running, carrying load, or performing athletic tasks, your performance depends on how well this central system organizes and transmits forces into your limbs.

This deep system operates through the combined influence of intra-abdominal pressure (IAP), coordinated transverse plane movement, and a well-aligned thoracolumbopelvic canister—the integrated position of the rib cage, spine, and pelvis. Together, they form what we call the respiratory engine, the internal mechanism that stabilizes the spine and drives power in movement.

Why It Matters

Every step you take is a dynamic negotiation with gravity. If your axial skeleton fails to maintain equilibrium, force leaks and compensations begin to appear. These small breakdowns lead to:

-

Loss of balance during walking or load carriage

-

Inefficient energy use, increasing fatigue

-

Stress on joints from poor force transfer

-

Greater injury risk due to instability in the center

The solution lies in learning to integrate spiral lines—the diagonal fascial connections between opposite shoulder and hip—and maintain axial equilibrium. When this central-to-distal relationship is intact, movement becomes smoother, stronger, and more efficient.

Core Concepts

The Axial Skeleton as the Hub

The axial skeleton does not just provide structural support—it’s a living, responsive pillar. The thoracic spine, lumbar spine, and pelvis must stay aligned, rotate efficiently in the transverse plane, and resist unwanted twisting.

Intra-Abdominal Pressure

IAP is the 360-degree pressurization inside the abdominal cavity, created through the coordinated action of the diaphragm, abdominal wall, pelvic floor, and spinal stabilizers. This internal pressure stiffens the spine, providing a stable foundation for the limbs to generate and transfer force. In Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization (DNS), breathing and stabilization are inseparable—they happen together from our earliest developmental stages.

The Respiratory Engine

The respiratory engine is the combined function of the diaphragm, rib cage, and abdominal wall working to maintain spinal stability while breathing. It supports rotation through rib movement and manages force transfer across the body during gait and loaded movement.

Transverse Plane and Spiral Line Integration

Rotation in the transverse plane is how the body resets tension and transfers force from side to side. This requires diagonal integration—thoracic rotation paired with pelvic counter-rotation—activating fascial spiral lines that run from one shoulder to the opposite hip. This diagonal “torque system” is central to walking, running, throwing, and ruck marching.

From Development to Walking

In early infancy, sagittal stabilization—keeping the spine steady—develops first. By about four to six months, rolling introduces transverse plane control and diagonal integration. By the time we walk, the thorax and pelvis are naturally rotating in opposite directions, creating alternating torque and storing elastic energy for each step. This developmental blueprint, which DNS uses as a model, is the foundation for efficient, balanced gait throughout life. When we lose this pattern through poor posture, injury, or sedentary habits, walking and load carriage become less efficient and more taxing.

Why Back-Loaded Rucking Improves Axial Integration

Ruck training—walking or moving under a weighted pack—places a deliberate, sustained load on the posterior chain and spinal stabilizing system. This back-loaded demand acts as a real-world amplifier for the very forces the axial skeleton must control.

When weight is placed on the back, the center of mass shifts slightly behind the base of support. This subtle shift forces the body to respond by:

-

Engaging the deep spinal stabilizers to maintain upright posture

-

Increasing intra-abdominal pressure to counteract spinal flexion or extension under load

-

Encouraging optimal rib-pelvis alignment to prevent over-arching the lumbar spine

-

Activating diagonal sling systems to resist unwanted trunk sway or rotation during each step

Because rucking is rhythmic and repetitive, it provides a unique opportunity to train the alternating rotation of thorax and pelvis that occurs in walking. The load magnifies any instability—if your axial engine is weak or poorly coordinated, you’ll feel immediate strain in the low back, hips, or shoulders. This “magnification effect” makes rucking a diagnostic tool and a corrective strategy at the same time.

Over time, back-loaded ruck training develops:

-

Endurance in the respiratory engine—you must maintain breathing and bracing simultaneously for the duration of the activity.

-

Diagonal integration strength—spiral lines must coordinate to stabilize the load across the midline during every step.

-

Anti-rotation control—as the load shifts with movement, the trunk must resist excessive twisting.

-

Postural reflex resilience—the nervous system becomes conditioned to maintain head, rib, and pelvis alignment even under fatigue.

Unlike traditional gym-based core work, rucking trains these qualities in a gait-specific context, making it directly transferable to daily life, hiking, tactical demands, or any activity where posture and load management are key.

Active Respiratory Mechanics Training

To maximize the benefits of rucking, active respiratory training focuses on:

-

Coordinating the diaphragm to brace and breathe at the same time

-

Mobilizing the rib cage for full rotation and expansion

-

Refining postural reflexes so the head, trunk, and pelvis stay stacked regardless of terrain or fatigue

This ensures that the respiratory engine works in harmony with the axial skeleton, allowing you to carry load without sacrificing efficiency or balance.

Key Takeaway

Your ability to move efficiently, breathe powerfully, and stay stable under load depends on the seamless integration of the axial skeleton, respiratory engine, and spiral line systems. Back-loaded ruck training—when performed with proper technique—strengthens this integration by challenging posture, rotation, and breathing under realistic, functional conditions. Combined with targeted breathing mechanics work, it ensures that every step you take is supported from the center out, creating a more resilient, efficient, and powerful body.