The Impact of Breathing Biases, Lateralization, and Neuromuscular Asymmetry on Jaw Structure and Craniofacial Development

Understanding how asymmetry in human physiology contributes to breathing dysfunction, craniofacial misalignment, and systemic health issues, and exploring the mechanisms and interventions necessary to restore balance.

Thesis Statement:

The body’s natural asymmetry, combined with neuromuscular and structural imbalances such as the Left Anterior Internal Chain (LAIC) dysfunction, leads to altered respiratory mechanics and craniofacial development. These dysfunctions cascade into airway obstructions, reliance on accessory breathing, and the need for interventions like CPAP machines to prevent further systemic damage. Addressing these interdependent issues is crucial for achieving structural and functional balance.

Test Your Comprehension Questions

- What is the Left Anterior Internal Chain (LAIC) imbalance, and how does it affect diaphragm function and posture?

- How does physiological asymmetry contribute to altered breathing patterns and craniofacial misalignment?

- Explain the mechanism by which mouth breathing and paradoxical breathing patterns lead to retrognathia and obstructive sleep apnea.

- What are the roles of the somatic and autonomic nervous systems in regulating breathing, and how do their dysfunctions exacerbate the condition?

- Describe the relationship between the diaphragm’s inefficiency and the over-reliance on accessory breathing muscles.

- Why does obstructive sleep apnea require the use of a CPAP machine, and how does it help alleviate the condition?

- How do structural changes in the rib cage and cervical spine impact the alignment of craniofacial structures and the airway?

- What interventions, both therapeutic and medical, are effective in addressing the structural and functional imbalances caused by altered breathing patterns?

Mechanism of Dysfunction: From Physiological Asymmetry to CPAP Dependency

1. Physiological Asymmetry: The Starting Point

Human asymmetry originates from:

- Organ Placement:

- The liver’s dominance on the right side provides structural support to the right diaphragm, making it stronger.

- This natural asymmetry creates an imbalance in breathing mechanics.

- Neural Lateralization:

- The left hemisphere of the brain influences right-sided motor control, reinforcing right diaphragm dominance.

- The right hemisphere, responsible for spatial awareness, often fails to adequately stabilize the left-sided postural chain.

This asymmetry is inherent but becomes problematic when imbalances exacerbate over time due to posture, environment, or developmental delays.

2. The Left Anterior Internal Chain (LAIC) Imbalance

The LAIC imbalance arises when the left diaphragm underperforms, causing:

- Thoracic Rotation: The spine and rib cage rotate towards the left due to right-sided muscular dominance.

- Rib Cage Positioning:

- Right Rib Cage: Internally rotated and compressed.

- Left Rib Cage: Over-expanded and externally rotated.

- Diaphragmatic Inefficiency:

- The left diaphragm loses its zone of apposition (contact with the rib cage), reducing its ability to create negative pressure during inhalation.

Consequences:

- The diaphragm’s reduced efficiency leads to over-reliance on accessory muscles (scalenes, sternocleidomastoid) for breathing.

- Altered rib cage positioning forces the cervical spine and craniofacial structures into compensatory postures.

3. Altered Breathing Patterns: Accessory and Paradoxical Breathing

When the diaphragm becomes inefficient, the body shifts to accessory breathing:

- Accessory Breathing:

- The neck and upper chest muscles compensate to lift the rib cage during inhalation.

- This results in shallow, rapid breaths that bypass the diaphragm’s efficiency.

- Paradoxical Breathing:

- The abdomen moves inward during inhalation due to poor diaphragmatic engagement.

Impact on Anatomy:

- Cervical Spine: Chronic overuse of accessory muscles pulls the head forward, disrupting cervical alignment and cranial posture.

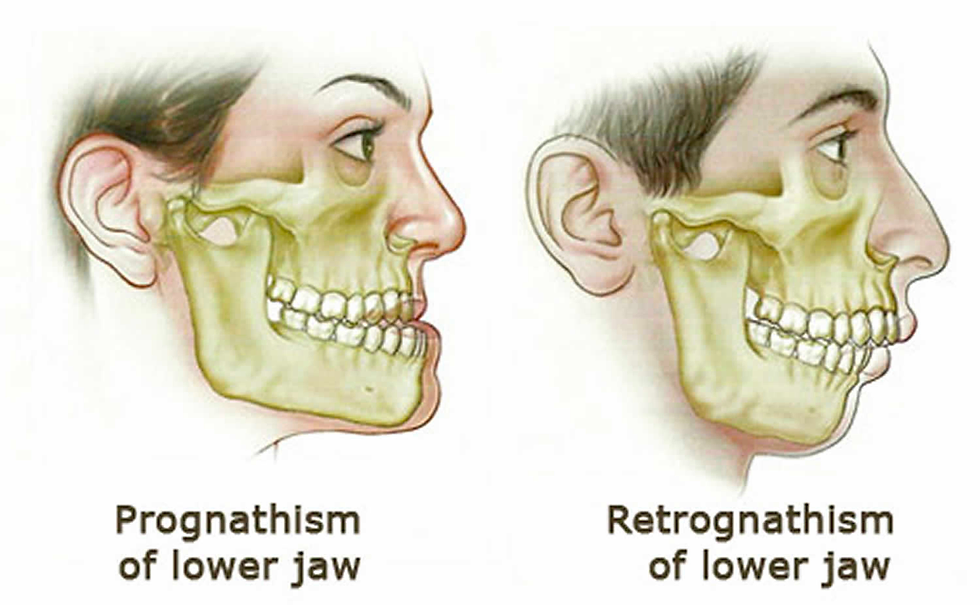

- Craniofacial Structures:Forward head posture causes the mandible to retract (retrognathia), narrowing the oropharyngeal airway.

- Airway Collapse: Weak tongue posture and high-arched palates (from mouth breathing) further reduce the airway size.

4. Mouth Breathing and Airway Compromise

When nasal breathing is bypassed:

- The tongue rests low in the mouth instead of on the palate.

- This eliminates the scaffolding effect of the tongue, leading to:

- A narrow maxilla (upper jaw).

- A high-arched palate, reducing nasal cavity space.

The combination of retrognathia and narrowed airways creates:

- Increased airway resistance.

- Higher likelihood of airway collapse during sleep (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea, OSA).

5. Obstructive Sleep Apnea: The Culmination of Dysfunction

OSA Mechanism:

- Airway Collapse:

- During sleep, the relaxed muscles of the tongue and oropharynx allow the airway to collapse, obstructing airflow.

- Disrupted Breathing:

- The brain detects oxygen deprivation, prompting micro-awakenings to resume breathing.

- Compensatory Over-Breathing:

- Chronic reliance on accessory muscles perpetuates shallow and inefficient breaths.

Systemic Effects:

- Reduced oxygen delivery impacts cognitive function, cardiovascular health, and systemic recovery.

- Chronic fatigue results from fragmented sleep.

6. The Role of CPAP Machines

A CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure) machine is necessary when:

- Anatomical Collapse:

- Severe retrognathia and maxillary insufficiency reduce the airway’s baseline size, making mechanical support essential.

- Chronic OSA:

- Repeated airway obstruction causes systemic oxygen deprivation.

How CPAP Works:

- The machine delivers continuous air pressure, forcing the airway to remain open during sleep.

- This prevents airway collapse, improving oxygen delivery and reducing sleep fragmentation.

7. The Causal Chain of Dysfunction

Step 1: Physiological Asymmetry

- Right diaphragm dominance and left diaphragm weakness create structural imbalances.

Step 2: Thoracic and Cervical Misalignments

- Rib cage torsion and forward head posture distort cervical and craniofacial alignment.

Step 3: Altered Breathing Patterns

- The diaphragm’s inefficiency shifts breathing to accessory muscles, creating paradoxical patterns.

Step 4: Craniofacial and Airway Compromise

- Mouth breathing and poor tongue posture lead to maxillary narrowing, high-arched palates, and retrognathic jaws.

- These changes reduce the airway size, increasing resistance.

Step 5: Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- During sleep, the compromised airway collapses, causing repeated oxygen deprivation and arousals.

Step 6: CPAP Dependency

- In severe cases, anatomical limitations necessitate CPAP to maintain airway patency.

8. Anatomical and Physiological Interconnections

Structures Affected by Impaired Breathing:

- Diaphragm: Loses efficiency due to asymmetry.

- Rib Cage: Rotational distortions create structural instability.

- Cervical Spine: Misalignment from compensatory breathing patterns.

- Craniofacial Structures:

- Maxilla and mandible become misaligned, exacerbating airway obstruction.

- Airway:

- Narrowing and collapsibility create high resistance during respiration.

- Nervous System Regulation:

- Somatic Nervous System (SNS): Controls voluntary movements like diaphragm contractions.

- Autonomic Nervous System (ANS):

- Sympathetic (Ergotrophic): Promotes active, stress-driven respiration.

- Parasympathetic (Trophotropic): Supports diaphragmatic, restorative breathing.

9. Key Takeaways

- Physiological asymmetry initiates a cascade of compensatory patterns that disrupt breathing and craniofacial alignment.

- The progressive dysfunction impacts the diaphragm, accessory muscles, craniofacial structures, and airway size.

- CPAP becomes necessary when structural and functional limitations prevent natural airway maintenance during sleep.